The standing room-only crowd at a recent community meeting to discuss the fate of St. Andrews Plaza on San Pablo Avenue, in Oakland, waited patiently as City Council Person Lynette Gibson Mcelheney and her accomplices outlined an unusual redevelopment plan. St. Andrews is a small parklet, literally a concrete container for a few trees on a triangle shaped slab of traffic-flow detritus. Its location on San Pablo Avenue, however, a rapidly gentrifying area of West Oakland adjacent to downtown, makes it a lynchpin in the city’s new aggressive pro-gentrification development for the San Pablo corridor.

The standing room-only crowd at a recent community meeting to discuss the fate of St. Andrews Plaza on San Pablo Avenue, in Oakland, waited patiently as City Council Person Lynette Gibson Mcelheney and her accomplices outlined an unusual redevelopment plan. St. Andrews is a small parklet, literally a concrete container for a few trees on a triangle shaped slab of traffic-flow detritus. Its location on San Pablo Avenue, however, a rapidly gentrifying area of West Oakland adjacent to downtown, makes it a lynchpin in the city’s new aggressive pro-gentrification development for the San Pablo corridor.

The St. Andrews Redevelopment Plan currently has one phase, which essentially consists of the destruction of the plaza. Mcelheney and the rest were straightforward about their topsy turvy rational for redevelopment that begins with leveling the targeted structure and has no concrete plan for reconstruction—they claim to be answering pleas from the community to bring a halt to the flow of homeless people and people with substance addiction to the plaza.

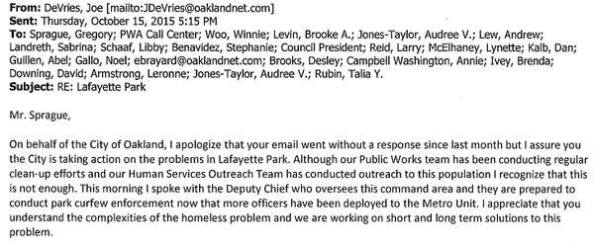

This was no mustache-twirling law and order villainy bullshit of old, though—at least not in public. In Oakland, city officials and politicians have learned the codes of gentrification discourse. Joe Devries, the Special Assistant to the City Administrator, Mcelhaney and her staff even referred to those who use the park as “historic residents”. They added later that the city had tried to lure them away with services, or help them improve the state of their lives, and by association, the park. But those historic residents “weren’t ready” to accept the help.

Devries, whose sole job seems to be the eradication of homeless camps, spoke about the city’s endless battle to find humane ways of dealing with homeless populations, where even sanctioned camps were a possibility. This was not the the much more honest Devries you find in these recently released emails, dutifully carrying out the whims of affluent Oakland residents in destroying homeless encampments and even making sure people don’t sleep in their cars in parking lots at night. Devries doesn’t seemed to be bothered by eradicating homeless encampments at the behest of affluent Oaklanders at all. You can be forgiven for thinking he even seems to like it.

Regardless, Devries described a painstaking process of extending aid and outreaching to the people using St. Andrews, all of which failed, unfortunately. There was no solution other than, coincidentally, using Devries favorite hammer, the eradication of the site.

After leveling the plaza, the city will build a fence around it, perversely decorated with art by and about children so as to sanctify the process and indict by association those opposing it. Clever manipulation of prevailing anti-gentrification discourse notwithstanding, the logical outcome of this act is quite obvious—that those people that currently use the park for whatever purpose will be scattered to other parts of the San Pablo corridor.

Despite saying all the right things, and fitting the idea in missionary clothes worthy of Mother Theresa, the bottom-line is that capital now requires the city to step in and eradicate one of the few surviving public commons of West Oakland’s historic population by force. Its no coincidence then, that throughout Devries’ introduction of the idea, one police officer after another was named as crucial to the design and implementation of the demolition project. The reality, that force, embodied in muscular urban design and policing, would take care of what affluent newcomers and developers could not do, was never occulted. Indeed, the number of police officers in attendance who were linked to the plan, was equal, if not greater, than the number of city planners and officials present at the meeting.

The fact that this was all being done for the sake of improving the look and character of the corridor was also in plain view. When one resident asked if the city would continue to remodel the area after the demolition, a non-profit minion was beckoned from the audience, and he jumped eagerly into the fray, speaking enthusiastically of bringing a fresh foods market to the area. Though he described it as a benefit to a struggling population, it more resembled a Trojan horse designed to ameliorate the rough math of depopulating the area of its unwanted people. A solution to the problem of food desserts, the only problem being that those who suffer from them because of geography and racism would be disappeared by the time it was built.

All of this isn’t to say that the city is moving only at the behest of capital and the affluent. Of course, many long time historic residents are ambivalent about the park for a variety of reasons. There is urine, feces, garbage, dumping, the entire gamut of what accumulates around outdoor areas used by the homeless and/or addicted population. These embattled communities, as some observed, have been complaining about the park for years. In previous years when there were fewer affluent, whiter people in the community, their opinions yay or nah have mattered little to the city of Oakland, though.

Though the crowd at the meeting was probably 3/4 white, several African Americans who identified themselves as historic residents spoke at the community meeting. They acknowledged the human dimension of the problems, while still wanting something to be done. It’s a pretty wide spectrum of opinion, regardless—some pretty authoritarian, some suspicious of the city’s true intentions, many sympathetic to the plight of people who use the plaza and acknowledging them as neighbors. But the city is taking advantage of the fact that these historic residents want relief from one burdensome situation in their neighborhood to beard their intentions and the rationale behind the sudden urgency of action.

Disinvestment and rapid gentrification have created a zero sum game for struggling communities of color which forces working and poor people to choose between dehumanizing options. They can let their neighborhood cohesion fall apart and become a dumping ground; or call in the city to use force to shuffle problematic people and situations. The truth, though, is probably clearer to historic residents than to anyone else. You can’t erase people, no matter how hard you try, or how superficially you convince people you have. They go somewhere else, they come back, they often simply stay in the neighborhood in one form or another. They certainly don’t suddenly attain the means to improve their situation.

My own experience at Biblioteca Popular, a community space liberated from the city nearly four years ago, has given me some insights into this cycle which West and North Oakland are currently enduring, and which the East is beginning to encounter. When we established our project–a community garden, meeting space and mini library run as horizontally as possible–our goal was to involve local poor and working class poc from the community in salvaging a vital resource that had been, through neglect, racism and apathy, closed and forgotten by the city. The Miller Library Building, a former library and school owned by the city, was completely abandoned at the time. Despite the city being bound by municipal ordinance to maintain the official historic building, it was ignored, fenced off, bolted shut and deteriorating rapidly.

There had been several generations of squats in the building. They were people from the very neighborhood, who had used the grounds and the building. They had lived there, but their use of the building and grounds revolved around their primary objective in life, which was scoring drugs and alcohol. In the process they extended and created, nevertheless, very real social networks that have enduring bonds. One squat after another had been tossed aside by police for over a decade there. When we found and [briefly] occupied the building in 2012, it had been completely abandoned for at least a year. But there’s no getting around the way it became empty when we found it–first through the violence of negligence, disinvestment and austerity. Then through the violence of police force.

The people who’d used the building moved on. They found other places to follow their life choices , but many stayed in the neighborhood. These squats and hang outs were rousted by police violence instigated independently, or when people, not knowing what else to do about objectively not-great stuff, called the police in. After about 2 years of running a pretty successful ongoing community-driven occupation of city land on the grounds of the Miller Library, these folks began to drift back to the block. This was mostly because for various reasons both practical and political, we do not engage the police in any way—the most salient being, of course, that we are an illegal occupation ourselves.

For about a year, our small collective of families that run and develop the space has struggled with the very real problems of having a sizeable group of people on the periphery who, for various reasons, lack significant control over their lives. The families raise children in cramped studios and one bedroom apartments, often earning a living by selling paletas, holding garage sales, or in low paid child care or restaurant work. One of the primary uses of the Biblioteca for them is to get themselves and their loved ones into an area surrounded by green and growing things, where there is some room to run around, or sit in peace, a distance from the street and the bustle of life in the Dubs. It’s a place to get to know people who have been living around the corner for decades but were never met. Pretty deep relationships, especially between neighborhood children, have thus developed.

The arrival of the group had a huge impact on these relationships to the space. The smell of urine, often feces, in areas used by toddlers, large amounts of bottles of alcohol and trash — the list is extensive. The area has been a dumping ground for years, and the presence of a group of people willing to make use of other people’s garbage exacerbated the impact. Heavy, open self-abusive drug use was ubiquitous.

All of this created many quandaries for local people and families in various stages of politicization who either helped run, supported or used the Bibliotheca Popular space. These are primarily poor and working class Latino people, who have nonetheless lived in the neighborhood for decades and are raising their children there. I rarely spoke to anyone of these folks who didn’t feel some level of empathy for the people making use of the area around the Biblioteca fence. But they also acknowledged the difficulty of raising children and going about their daily lives with such a high level of drama and problematic behavior occurring in front of their homes. Many began to consider the value of having the Biblioteca open as a community space.

The amount of time we spent cleaning the very foul messes some people left increased to the level that we did little else when we came there to do work. People began to avoid the block, and to put it charitably, it was not a place people were enthusiastic about sending their children to. That’s not to say the same group giving us daily headaches weren’t pleasant with us, were not vibrant souls, nor had great stories to tell. They even did some of work there when they were in good spirits. And they too practiced a wide spectrum of behavior and choices. There was a substantial debate about hygiene and behavior, and a lot of it was on the grounds not only of stability, but of respecting the grounds where people had created some pretty impressive positive feats.

Through this rough patch, we had a pretty great advantage, though. We were outside, in a commons that belonged to no one, where we could interact with one another as fellow human beings and life-long neighbors. We made full use of this tool, opening up dialogue as often as possible, and without any specific methodology in mind. We used all modes known to humankind—begging, pleading, reasoning, blowing up and making peace, among many others verbal and non-verbal. Natural leaders amongst the group of addicts and homeless people emerged and we had many, many conversations with them. Over time, an extended family of former addicts and relatives who remained close, though troubled by the trajectory of their loved ones lives, also helped out and continue to do so. None of this was easy. We sufferedthrough some very difficult periods where we wondered if we could maintain the space and if we even wanted to. But over time, and with a lot of very open talk, we reached an equilibrium that respected the rights and needs of those on the margins while acknowledging the fragility and importance of what neighbors had constructed.

The people who share the area with the Biblioteca don’t necessarily consider themselves members of the collective. But they do consider themselves boosters and supporters. They stay on one side of the grounds, and do their best to clean up after themselves and keep certain behaviors on the DL. The integrity of the grounds and garden are respected, no garbage or other waste actions are conducted there anymore. The difference has been staggering, and its been consistent for many months now, long enough to expect it to continue, perhaps with hiccups now and then. It’s been remarkable to watch people facing homelessness and addiction self-organize to minimize their negative impact and create some level of stability for themselves and has really altered my baseline of what’s possible.

This group also receives some positive benefits by falling into balance with us—access to the community drop off box, food and clothing donations, and all the books they can read. They can enjoy the garden and grounds with the caveat that it’s a drug and alcohol free safe-space. But there’s one intangible benefit, perhaps significantly more important than the rest–they are allowed the space and access to do good things in the midst of whatever it is they are going through in their lives. A significant number of this group have done real, meaningful and lasting work in the garden, moving a huge pile of wood, for example, that had been left off for us to use to another area where it wasn’t in the way, planting an entire crops of greens which at the moment is at its most prolific, cleaning up not just their area around the space, but he entire area around the space. They were happy to do these things, to be allowed to be humans with agency and the right to help out others and create beauty.

Admittedly, not all of us like what goes on in front of the garden and community center. But the reality is that much of what city and state institutions consider rehabilitation is based on a model that people can and want to change the way they live. We have learned that is not necessarily the case for some people; breaking up camps and congregations like this with the fig leaf of “outreach” is simply a way to do the brutal work of monied interests while lying to oneself about the goals and outcomes. Some people can move on, some people can’t and may never be able to. And if that’s the case, there is no point in simply herding those that can’t move on to another place in the interest of illusory peace of mind. THe reality is that there are generations of trauma here, and they have been exacerbated in recent decades. Our goals should be to reduce and nullify the trauma for future generations while acknowledging that for some today, that trauma has already done its work.

Recognizing this, we have realized that the benefits of patient engagement exceed the inconvenience. When I have talked to one of the main neighborhood organizers about our magnificent feat of human engagement, her eyes light up. It’s hard to believe that merely through dialogue we made room for each other in a world none of us have much control over. Surely, if we had violated our principles and endangered the community by calling the police, we would have had a good chance of “getting rid” of these people quite quickly.

But we gained far more value from doing the hard work of human engagement and so did the neighborhood. We managed to keep all historic residents where they need to be, in the community they grew up in, using a reclaimed resource that some of them used as a library or attended school in when they were children. We kept our community space clean and safe. Perhaps more important than any one of those things, we retained our humanity by refusing to call armed thugs to do our dirty work for us. The sense of accomplishment in participants, and indeed, the hopefulness that seemingly immutable urban situations can be dealt with by ordinary people, is priceless.

But we gained far more value from doing the hard work of human engagement and so did the neighborhood. We managed to keep all historic residents where they need to be, in the community they grew up in, using a reclaimed resource that some of them used as a library or attended school in when they were children. We kept our community space clean and safe. Perhaps more important than any one of those things, we retained our humanity by refusing to call armed thugs to do our dirty work for us. The sense of accomplishment in participants, and indeed, the hopefulness that seemingly immutable urban situations can be dealt with by ordinary people, is priceless.

Posted on January 30, 2016

0